I believe there is something out there, watching us.

Unfortunately, it's the government.

Woody Allen

The fact that my press trip to Graz got cancelled last-minute was to be expected. There’s a certain predictability to these “strange and uncertain times”, as most emails tend to read these days. If I wouldn’t know any better, I would have thought the cancellation was staged as part of the concept of Steirischer Herbst 2020. But I don’t want to sound too suspicious here. Although there is a certain joy to be found in missing out on things (lifestyle magazines call it "jomo"), cancellations are usually no joke. The cultural sector is suffering immense economic losses due to the Covid-19-regulations, with little recovery in sight. In many countries, this situation has sparked a heated debate about the “necessity” of art and culture, and how much a society should care about its artists. Art as a ‘non-essential’ profession has by now become a widely proclaimed view in conservative circles. On the other hand, various cultural manifestations are being cancelled and censored in fear of rising tensions and possible reprisals, from a Fawlty Towers episode to a Philip Guston retrospective. Both sides of the ideological spectrum are caught up in a politics of cancellation, a cancellation culture problematic in and of itself, which should be met with elaborate criticism and forms of resistance.

In many respects, therefore, I’m glad to see Steirischer Herbst taking place in 2020, which surely hasn’t been an easy feat. For the third year in a row, Ekaterina Degot is acting as director of the festival, clearly leaving her rather provocative stamp on the identity of Europe's oldest arts festival. This time around, you no longer have to bother about running from one venue to another: you will receive convenient notifications about any upcoming events on your different devices. Via the website or designated app, the festival moves with you, across different screens, streamed smoothly to your ultra-wide HD smart television at home or to your smartphone on the commute to work. Arguably the cultural variant of home delivery, does a festival-on-demand format also work in practice? Does it reduce avid festival goers to passive couch potatoes?

Luckily there's still plenty of things to see and do in the city of Graz itself. The title Paranoia TV not only turns Steirischer Herbst into a media channel, but it reflects Degot’s typical tongue-in-cheek approach that was also present in last year’s Grand Hotel Abyss. Her opening speech came in two different versions; one pre-recorded and shown on different screens in cultural venues and stores throughout the city, while the other happened in real life at Graz’s Orpheum Theatre. On the day of the opening, however, the regional chapter of the far-right populist political party FPÖ sent out a press release denouncing the entire festival for its ‘unnecessary’, ‘grotesque’ program and ‘greatest possible decadence’ in times of crisis, a statement that is once again symptomatic of the ideological fissures present in current society. It’s hardly surprising since social media accelerates today’s polarizations, which further undermines the possibility of establishing a public forum, the very root of democracy. In the face of these worrisome developments, was it ever a clever rhetorical move to reprofile an arts festival as a media consortium called Paranoia TV? Does it offer us a way out of said impasse? Before addressing these questions, let’s first take a curious historical detour.

Influencing machines

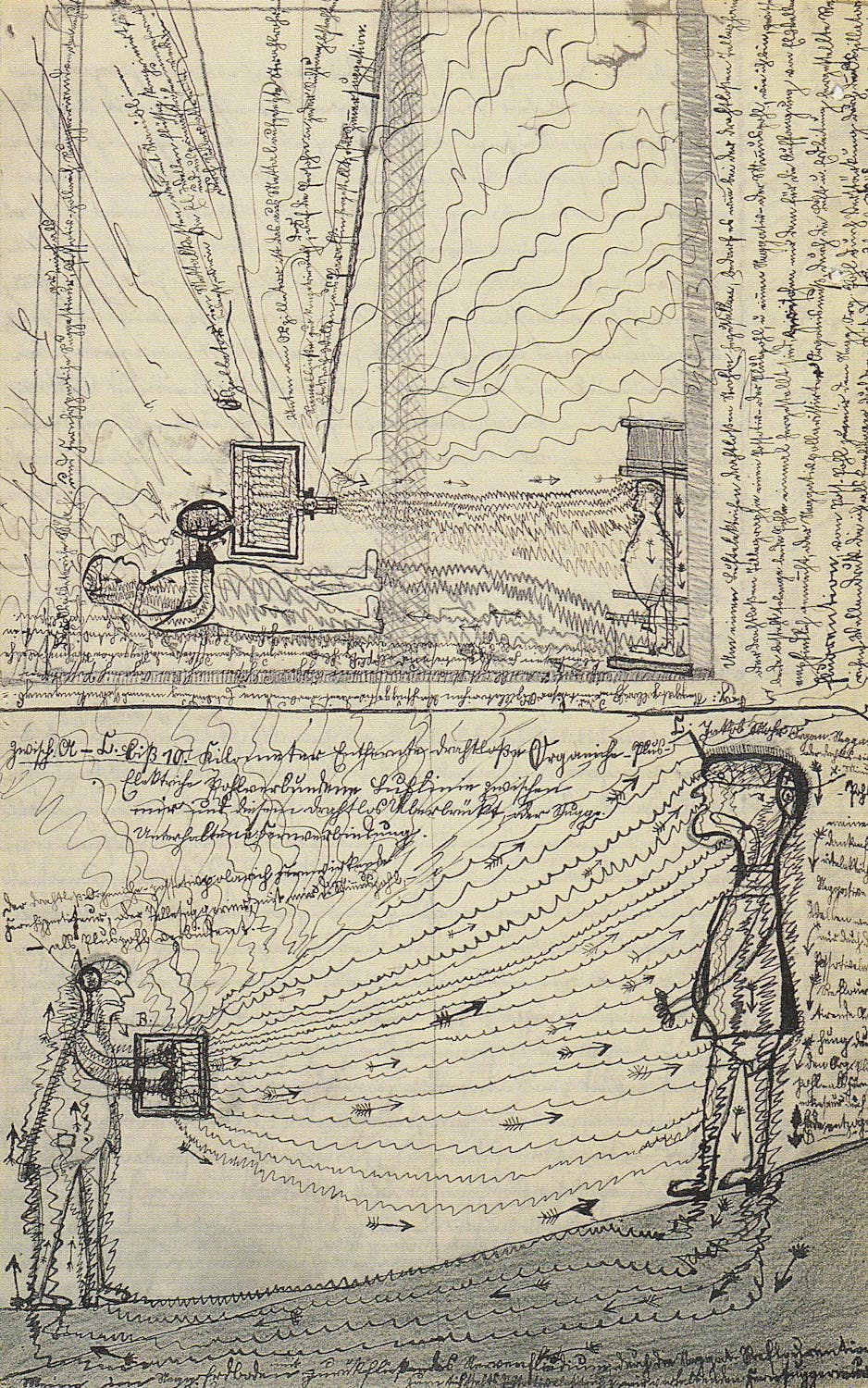

The famous Prinzhorn collection in Heidelberg contains a fascinating drawing titled Beweise (Proofs) made by schizophrenic psychiatric patient Jakob Mohr and dated 1910. It depicts two people facing each other, one holding a box or device of sorts (marked with the letter B) emitting invisible rays or waves represented by black, curved lines running from subject A to subject C, in a continuous feedback loop. What we are looking at is the “influencing machine” that Mohr believed was controlling his daily life. Panically afraid of the “negative fluorite-electric thought waves” enforced on him, he would wrap himself in a coat made out of tin foil.

Hans Prinzhorn, a psychiatrist and art historian, built his collection out of a fascination for the “borderland between psychopathology and art”, thus combining both of his passions. Besides their apparent therapeutic nature, Prinzhorn noted that many of the artworks created by his mentally ill patients were in fact holding up a mirror against mainstream society. And isn’t that exactly what we expect all great art to do?

Jakob Mohr’s paranoid “passivity delusions” were first studied in 1919 by Viktor Tausk, a friend and colleague of Sigmund Freud. His influencing machines still resonate with our present moment, over a century later. Mohr’s visions have become even more ominous. Simply think of the 'plandemic' videos, the Covid-19/5G conspiracy theories and numerous other types of misinformation that are widely circulating today. It would be too easy or outright positivist, however, to dismiss those beliefs as mere superstitious nonsense or ridicule them as the far-fetched chimera’s of a handful of lunatics on the fringes of society. What are they the symptoms of? Prinzhorn in 1921: “Given the great speed with which cultural forces become history today, the unperceptive person accepts as historic fact what until yesterday he believed he could safely ignore as the phantasmagoria of isolated enthusiasts.” The lack of a proven causal relationship between mobile network technology and global pandemic, for instance, doesn't mean there is no correlation to be found. The use of 5G networks could significantly enhance the accuracy of geolocation data and, with it, the possibility of monitoring individual and collective mobility. No paranoid fantasies needed there. With our ever-growing daily dependence on digital technologies, big data also means big business. So if it’s not for the greater good of public health or safety (as in the Covid-19-crisis), the idea of fully automated global surveillance is, ever more so, commercially motivated.

That is to say, there’s a method to Mohr’s madness. His “influencing machine” recurs in many other instances of paranoid delusion, like Freud’s controversial Schreber case. It is very often related to the manipulative use of technologies that were en vogue at a specific point in time. The Chief character in Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is yet another example to be drawn from popular fiction. But these convictions don’t need to be considered pathological per se. In activist Jerry Mander’s manifesto Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television (1978), we read: “[T]here is no question that television does what the schizophrenic fantasy says it does. It places in our minds images of reality which are outside our experience. The pictures come in the form of rays from a box. They cause changes in feeling and ... utter confusion as to what is real and what is not." From a present-day perspective, one can think of the infamous simulation hypothesis, or the philosophical “brain in a vat” thought experiment that Silicon Valley yuppies find themselves so obsessed by. The only thing here is that today’s malins génies or influencing machines are no longer as clearly visible or identifiable as they were in Mohr’s days. Their physical appearance is much less present, although their operations have become more ubiquitous, pervasive, ingenious and algorithmic.

We always run the risk of merely psychologizing paranoia, reducing it to the deranged mental states of a number of individuals. It is well worth taking the psychopathology of everyday life into consideration as well. Its symptoms are more far-reaching than we tend to believe. Scientific studies have pointed out that almost a quarter of the population experiences regular paranoid thoughts. Does that even surprise us? Globalized terrorism, economic austerity and pandemics just add fuel to the fire, making such emotional dispositions even more widespread, with ever-increasing polarization as a direct outcome. Mostly irrational feelings of fear and suspicion are as contagious as a virus is, but the invisible enemy is no longer the disguised KGB-spy or totalitarian Big Brother of yesteryear. The current enemy lives amongst us, but is nowhere to be found. So, could it be that we are living in the age of paranoia? Has the exception become the rule, and our mind a technopolitical battlefield? And are newly emerging technologies fuelling delusional fantasies, even more than they have ever before?

Canary in the coal mine

Back to Steirischer Herbst, a festival that has always been utterly generous in its artistic programming. 2020 is no different, with contributions ranging from video screenings and artist talks, online games, giveaways, podcasts, performances and conferences. And for the haters out there: it’s outright wrong to state that the festival has lost sight of the general public. There are various ways of navigating this festival, depending on everyone’s personal preferences.

The home edition of Steirischer Herbst contains a kind of gaiety and cheekiness that yours truly is particularly fond of, especially in these rather dark times. The campaign launch for Paranoia TV happened through a digital avatar of Sigmund Freud, the poised master of suspicion. And yes, to complete the picture, his virtual appearance definitely looked unheimlich, which is exactly what the 2020 edition purports to be: “a platform for the uncanny and disturbing.” The artistic line-up, then, looks impressive once again - no concessions seem to have been made here. Most of the video works were commissioned or produced by the festival and split into different episodes, much like a soap opera. Unfortunately, I can say very little about the festival events that actually took place in Graz, so let’s look back at just a few of our favourite tv-moments.

Hito Steyerl took inspiration from Tatort, the longest-running and most popular tv-drama in German-speaking Europe. Traditionally, people like to enjoy a new episode of their favorite Krimi every Sunday, from their sofas at home or in a bar with some friends. But even Tatort seems to be suffering from the pandemic — a fact almost as unsettling as the melting of the permafrost. Steyerl is staging actor Mark Waschke, “star of Tatort’s Berlin series, [talking] about AI actors, avatar animation, police brutality and racism, G. W. F. Hegel, and what it’s like to be a TV cop on furlough.”

Most directly dealing with this festival edition’s tagline is Belgian artist and performer Diederik Peeters. His Dr. Delusion Show consists of three videos, in each of which he is presenting curious pathological cases: the Cotard’s or “walking corpse” delusion, the Doppelgänger syndrome and the rare Frégoli disorder. There is something comically awkward about his show, with the use of puppets and Peeters’s rhetorics only adding to the uncanniness of it all. Surreal, eery and morbid visions reoccur in the computer-generated imagery of Rana Hamadeh, a phantasmagorical danse macabre. But there’s always still hope. Ahmet Ögüt made a new video essay titled Artworks Made at Home, a journey through recent art history — ranging from Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975) to Hiwa K’s Cooking with Mama (2008) — which testifies to the inventiveness and resilience of domestic labor.

The festival program has been compiled with great care and most artistic contributions contain a strong sense of urgency in the light of today’s global crises. Clemens von Wedemeyer, for instance, made an intriguing new video piece showing an emergency drill simulating the capsizing of a ferry. A voice-over reflects on the ways in which we deal with catastrophes or moments of crisis, often falling back on pregiven, predictable scenarios. For good or bad, technology is increasingly being used to manage and control these states of exception, making it look like beta-testing a software program. Filmmaker John Smith, in his typical style, continues to push the boundaries between documentary and fiction in three new shorts, shot from his hotel room. A cityscape of London’s financial district is paired with fragments of speeches by Boris Johnson, attempting to minimize the gravity of the situation. Please move along, nothing to see here.

The discursive part of the festival program is equally overwhelming, featuring names such as Silvia Federici, Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, Milo Rau, Achille Mbembe and even a world-wide “memorial carnival” for the dearly departed author and activist David Graeber. Also noteworthy is a series of panel talks titled The Three Plagues, hosted by the talented and amiable writer-curator Adam Kleinman. Unfortunately, watching a mosaic of talking heads isn’t exactly the most enticing experience in times of online content overload.

It takes a whole lot of courage — artistically, intellectually and organisationally — to come up with such a hefty festival program in the current climate. That’s already an important merit in itself. Instead of serving political agendas, how can an arts festival create a forum for critical or dissenting voices? Whether creating a buzz or sparking controversy, Ekaterina Degot and her team have persistently stood up to society in the previous years, delivering a thoughtful comment on civilization and its discontents. And all praise for that. Setting up an interdisciplinary arts festival in these times is therefore much like whistling in the dark. As long as these whistling sounds can still be heard, it means that we are still awake and alive. What we should be most worried about is the moment when everything starts falling silent, like a canary in the coal mine. It’s what Kurt Vonnegut said in a 1973 Playboy interview:

“when a society is in great danger, we’re likely to sound the alarms. (...) You know, coal miners used to take birds down into the mines with them to detect gas before men got sick. The artists certainly did that in the case of Vietnam. They chirped and keeled over. But it made no difference whatsoever. Nobody important cared. But I continue to think that artists — all artists — should be treasured as alarm systems.”