Alles over kunst, dat is de baseline die we bij HART bezigen. Het is een weloverwogen boutade, want zelfs wij die de kunsten intens volgen kunnen nooit alles zien, laat staan over alles schrijven. Het is een onvervulbare ambitie, maar meer dan dat is het een uitnodiging aan de kunstwereld om actief deel te nemen aan het platform dat ons tijdschrift wil zijn. Naast een vaste kern van redacteurs nodigen we daarom ook andere schrijvers uit om bij te dragen aan HART, schrijvers én kunstenaars, want het is een misvatting dat deze laatsten zich enkel beeldend zouden uitdrukken.

Voor de derde bijdrage uit deze reeks in samenwerking met Netwerk Aalst laten we het woord wederom aan schrijver-in-residentie Agnieszka Gratza, die deel uitmaakt van het initiatief The Bodies. Lees hier het tweede deel van Agnieszka Gratza.

25.11.2021

Two trips around the moon since the Bodies finally got to meet IRL in Aalst, it’s about time to put pen to paper. And November 25th is as auspicious a date as any to resume writing this chronicle. I remember fashioning extravagant hats for the feast of Saint Catherine, the patron saint of unmarried women, as a teen growing up in French-speaking Canada. This joyful occasion, which was once a significant date in the Christian calendar, has since been eclipsed by the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, gradually attracting more and more media attention.

Was it purely coincidental that the UN General Assembly chose this particular day to raise public awareness of the issue, on the eve of the new millennium? The hagiography of the saint, otherwise known as Catherine of Alexandria – tortured, sentenced to death by a breaking wheel (her symbol) and, when all other methods failed, beheaded at the age of 18 for refusing to renounce her faith and yield to the advances of a powerful man (emperor Maximian) – makes her sound like the victim of harassment and femicide. She is not alone in this; reading between the lines, the Golden Legend is replete with accounts of sexually motivated violence perpetrated against women, worthy precursors of the MeToo movement.

Let it not be said that the advice given us by a well-wishing native of Aalst, who used to live a stone’s throw from our base, went unheeded. ‘Before, going to Netwerk Aalst was like going to Mars,’ José Gavilan reminisced over coffee at the long wooden table, which witnessed a heated exchange or two during the three-day-long meeting of the Bodies. ‘The current expedition leader changed all that,’ he hastened to add, tactfully. And yet, the abiding perception of Netwerk Aalst is that the institution is something of a ‘bubble’, its musical and artistic experiments simply too far out to speak to the denizens of Aalst.

‘Perhaps if we’re not connecting to the community, we should do whatever the hell we want?’ it dawned on Jeremiah Day. This suggestion and its dizzying implications rather reminded me of Dostoevsky’s hero grappling with the startling realization that ‘If God is dead, then everything is permitted’ in The Brothers Karamazov. Imagine a brave new world where artists did not have to think up ingenious ways to connect with the public, to reach out to the broader community, to somehow contribute to society – one where they did not have to concern themselves with audiences at all.

You may legitimately be wondering: ‘What has any of this got to do with November 25th?’ I’m getting there. For Gavilan, who has long been active in various civil society organizations that aim to bring different communities together, the problem with Netwerk Aalst has to do with a certain lack of clarity when it comes to communicating what it does in posters and other such promotional materials. One way to remedy this, according to Gavilan, would be to seize such opportunities as present themselves to publicize Network’s activities through different media channels. Take, for instance, the upcoming International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women; what better way to draw attention to the exhibition currently on view?

Friedrich Holländer’s If I Could Wish for Something, a Weimar era song interpreted by Marlene Dietrich, confusingly lends its title to Dora García’s solo show, the accompanying publication in the form of a ‘little red book’, and her latest documentary film, screened on a loop inside the exhibition space. By turns rousing and melancholic, the soundtrack of the film, seeping through the makeshift walls of the purpose-built black box where we had watched it on our first morning together, was a constant reminder of its powerful content. Just over an hour long, the documentary weaves together footage filmed during feminist protests that took place in Mexico City over the past few years and more intimate exchanges with trans artist La Bruja de Texcoco culminating in her performance of the theme song ‘Nostalgia’, which nods to the refrain of If I Could Wish for Something (the song).

Femicide, the most extreme form of violence against women that the protesters denounce in the film, has sadly gained currency in the local news ever since the former mayor of Aalst was bludgeoned to death by her companion in the summer of 2020. Ilse Uyttersprot, who served as mayor from 2007 to 2012, first rose to notoriety when a video of her dalliance in a Spanish castle tower went viral. Unabashed, the Christian Democratic and Flemish party representative sported an outfit with a tower motif as her ‘disguise’ at the next Aalst carnival, during the final year of her stint as mayor.

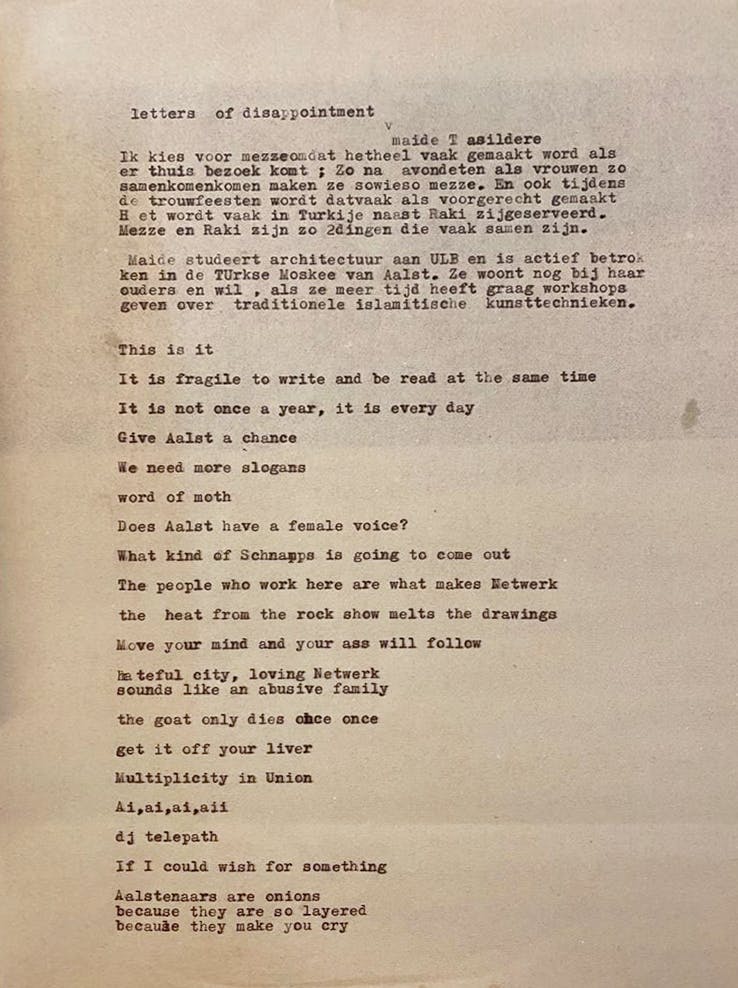

To my knowledge, Christian saints were not catasterized – that is to say, turned into constellations, stars or other celestial bodies – unlike some of their hard-done mythological counterparts, more sinned against than sinning. Entire compilations of their ‘complaints’ and ‘laments’ have come down to us, testifying to the popularity of this literary genre in the Middle Ages and beyond. Dora’s growing collection of ‘letters of disappointment’ by the likes of Hannah Arendt, Rosa Luxemburg and Alexandra Kollontai – the Soviet revolutionary, diplomat and women’s rights advocate at the heart of If I Could Wish for Something (the exhibition) – springs from the same fertile soil.

My favourite of the letters, which we took turns to read out at an event open to the public, was penned by Clara Zetkin. In it, the socialist leader and feminist activist debunks the so-called ‘glass of water theory’ often (and incorrectly) attributed to Kollontai – the author of The Autobiography of a Sexually Emancipated Communist Woman, admittedly – according to which, for a communist, the satisfaction of one’s sexual needs should be as natural as drinking a glass of water. (‘Or beer, for that matter,’ a Carnavalista might say.) Dora herself did a mean impersonation of a disapproving and disappointed Vladimir Lenin quoted by Zetkin, in one of his rare pronouncements bearing on the women’s question.

The city’s claim to fame, its beloved Carnaval, proves a divisive topic even among birds of a feather. The people of Aalst are firm in the belief that no one who is not from there can really understand what it’s about. We certainly try. Our guide through the underworld of Carnavalhalls, packed full of creepy, outsized Styrofoam figures biding their time, turns out to be a former traffic control officer who asks us to excuse his perfectly adequate English. ‘To airplanes, you don’t speak much,’ Vanessa Müller quips. But ensuring the orderly emergence of the 56 official floats that are stored there is quite an operation, by the sounds of it. Bianca Baldi muses about what it would be like to have to reconstruct the city of Aalst on the basis of a float sent into the future as a time capsule.

The riotous event means different things to different people, depending on their age group, gender and background. ‘It should be a multicultural feast, but in fact, it is 95% white,’ our guide admits. A young woman, who isn’t originally from Aalst, tells Jeremiah how she constantly worries about the safety of her girlfriends during those three days of drunken revelry, when men overstep boundaries and feel that everything is permitted. Shot in Aalst, Wendelien van Oldenborgh’s black-and-white short Horizontal (1997), paints a grim picture of the morning after.

One of my more pleasant memories of the Aalst Carnaval in its 2020 edition hinged on bumping into Ilse and Hugo, whom I got to know while hanging around Netwerk Aalst’s bar, at the Moker. The cosy bar à manger, which came highly recommended by an enthusiastic Carnavalista within Netwerk Aalst’s team, was serving fancy hotdogs straight off the grill. Most of the furniture had been removed for the occasion, in anticipation of carnivalesque excesses, so much so that I barely recognized the place when the Bodies gathered inside its rose-coloured interior for the first in a series of delicious and imaginative meals, drawing on different culinary traditions, to which we were treated over the course of our three-day stay in Aalst by Moker’s Annelien Vermeir.

More than just a foodie, Vermeir is a chef with a vision. And yet we could not help but notice that the only woman from Aalst whom we got to interact with was ostensibly there, well, to feed us. (In their defense, it would appear that our ground control people tried but were unable to find female officials willing to come and talk to us.) So, should we make ‘the women’s question’ our own for the remainder of The Astronaut Metaphor, as some Bodies have tentatively suggested? And, if so, how can we reframe the question to keep with our gender-fluid, cyborg age? The answer may well lie with Annelien, as we brace ourselves for some extravehicular activity, away from the comforts of our space station, in the year to come.