Aphasia is a multidimensional project by Jelena Jureša that seeks to find a language to counter the mechanisms of silence used to protect those who have committed crimes of unimaginable cruelty. Galit Eilat describes how the immersive performance of Aphasia eventually turns spectators into participants, through the music that persuades the audience to join in.

Aphasia is a medical term that refers to a disability in language skills, for example, the loss of the ability to speak, understand, read, or write. It’s a symptom that results from neurological damage to the brain. Aphasia has a wide range of symptoms, but the common feature is speech problems that do not result from damage to the organs of speech or hearing.

The project has two episodes. The first is a feature-length film that began its itinerary at Argos, the center for visual arts in Brussels, in 2019. This summer, it was also exhibited at Manifesta in Pristina. The film is a disturbing investigation into the representation of violence and the violence of representation. The second episode, which I address in this text, is an immersive performance that was presented for the first time during the Kunstenfestivaldesarts festival in Brussels in May 2022.

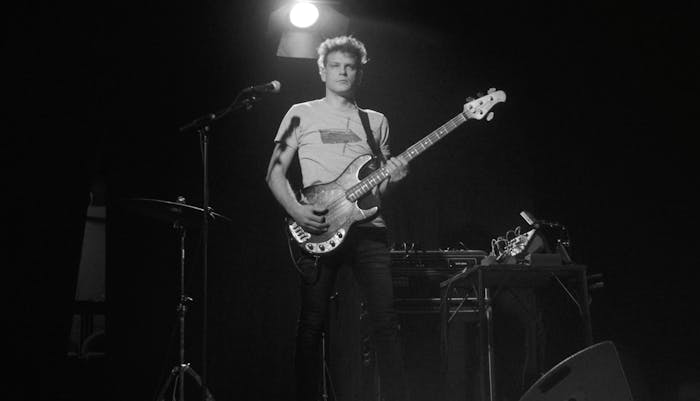

A dark hall empty of chairs or benches welcomes the members of the audience who enter to see the performance. Strumming on an electric guitar confirms we’ve entered the right place. A few seconds pass, our eyes accustom to the darkness, and we see three stages towering high above the heads of the audience. The silhouette of the guitar player can be seen on one of them. The tempo of the music increases, but the motif remains unchanged. Some audience members move to the rhythm of the music, while others wander around or stand restlessly, waiting for the show to begin. It will take a few more minutes for everyone to realize that the show has already started. In fact, the show began with the entrance of the first guest.

The hall where the performance takes place is designed as a black box with elements reminiscent of a nightclub; like the white cube of the modern art exhibition space, the black box is not designed as a specific nightclub but as one that could be found anywhere or nowhere. A nightclub holds the potential of unlooked-for experiences, even if on stage the script is known in advance – it’s time-bound, and actors shape the experience as a whole. But nightclubbers enter a club as participants, not as spectators. And a show allows the audience to experience a narrative written in advance, similar to a ceremony or ritual in which the priest or shaman is supposed to have guided the audience to a safe shore by the end of the event.

Another guitar player joins from a stage on the opposite side of the hall, and several grouped monitors turn on, one after another, playing short black-and-white clips in loops. Sequence after sequence, we watch the same scene unfold: a group of men standing in a circle, playing instruments or clapping their hands, while one man is pushed to the center of the group to dance. The clips are taken from different periods, geographies and situations, but all follow the same principle: a man dances and moves in front of a group. Since it’s unclear where the footage is from, it remains uncertain whether the dancer is performing by choice or under compulsion. Is he pleased to dance or dancing to please others? [1]

The video material changes: from the back of a palm moving casually, followed by a hand holding a burning cigarette, to Hannah Arendt smoking a cigarette, or a child attacking an apple with his teeth, biting into it obsessively.

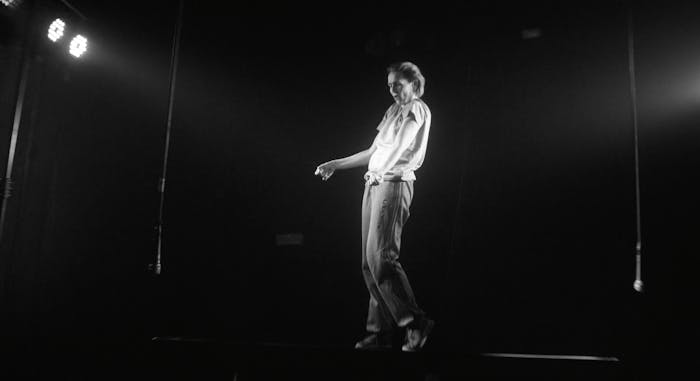

A woman figure appears on top of the third stage. Perhaps the performer was there the whole time, waiting in the darkness? And just like the two guitar players, she is wearing an outfit reminiscent of a military uniform, but in a metallic gold color. She tells us about a famous club in Belgrade where a man called DJ Max performs. DJ Max is the man who was photographed by the war photographer Ron Haviv on April 2, 1992, in Bijeljina. The photograph captures a young man with his back to the camera, holding a cigarette in his raised hand, standing on one leg. His other leg is aimed at kicking the body of a woman lying on the sidewalk.

Two weeks after the massacre in Bijeljina, Haviv’s photo was published in Time Magazine under the headline ‘The killing continues.’ The publication caused an international uproar. The picture of DJ Max standing with his back to the camera came to represent the brutality of the massacre in Bijeljina carried out by the Serb Volunteer Guard (SDG), also known as Arkan’s Tigers. [2] On April 3, Serbian forces removed the bodies left over from the slaughter in anticipation of the arrival of a Bosnian government delegation tasked with investigating what had happened the day before. The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the Office of the Serbian War Crimes Prosecutor verified between 48 and 78 deaths. Post-war investigations documented the deaths of just over 250 civilians from Bijeljina. Arkan’s Tigers commander Željko Ražnatović was indicted by the ICTY in 1997 for numerous crimes against humanity and serious violations of the Geneva Conventions and the laws of war, including active participation in the ethnic cleansing in Bijeljina and Zvornik in 1992.

After the war, the photos taken by Haviv were used as evidence – often of critical importance – in criminal prosecutions in the ICTY. Several witnesses identified the soldier in the photo as Srđan Golubović, a former member of the SDG, known as Max on the battlefield, and DJ Max in Belgrade. In September 2012, at the request of the Serbian War Crimes Prosecutor’s office, the Belgrade police investigated Golubović’s role in war crimes committed in Bijeljina. Golubović was arrested; narcotics and firearms were found in his apartment, but he was released without trial.

Nightclubs in Belgrade have a dark past, especially when it comes to the genre nicknamed Turbo-folk, whose production and distribution was supported by the Serbian government as propaganda in the service of the state. A typical example of the use of Turbo-folk from the 90s is the music video for Ceca’s ‘It’s Not Monotonous,’ in which she is filmed playing with a live tiger cub while she was married to the leader of the SDG. In the performance of Aphasia, we’re confronted with a sexualized female body through the apparition of Ceca’s turbo-folk stage persona, brought to life by the powerful acting of Ivana Jozić.

The Aphasia team, who lived through the breakup of Yugoslavia and the Balkan wars, has a message for us – a message about the ways in which the marks of wars never fade, and as a shadow, they come to life, with the weakest trigger of light. Within this meticulously constructed relationship – made of sound, moving image and storytelling – Jureša sheds light on the complexity of collective violence and the aftermath of trauma. The music, written and played by Alen and Nenad Sinkauz, fights back against Turbo-folk’s beat.

While watching Aphasia, it was impossible not to think about the war on the sovereignty of Ukraine and how that war is again hitting Europe’s eastern borders. I looked around and wondered if the people around me understood that they were living in war times; even if they aren’t sent to the front and will never hear a single gunshot, this war will leave its marks, changing them forever.

In Aphasia, Jureša explores the range of roles conventionally assigned to the spectator – from passive onlooker to active participant, from bystander to actor. This tension between passivity and aggression is maintained throughout the performance, until the audience, which has been on its feet for an hour, begins to dance to the rhythm of the music while a smoke machine envelops the hall in thick red smoke. Aphasia eventually turns the spectators into participants through the music that persuades the audience to join in. None of this happens without resistance; part of the audience chooses the position of an observer from the sidelines. But the ones that do participate become partners, turning the performance into an event.

The fact that the protagonist in Haviv’s famous photo, which has become the symbol of the genocide committed by Serbia in Bijeljina, was never held accountable for his crimes, will continue to bother us long after the performance ends. [3] As Michael Rothberg claims in his book The Implicated Subject Beyond Victims and Perpetrators, Aphasia tries to break through the prevailing perception of the categories of victim, perpetrator and bystander, which do not adequately explain our relationship and complicity with injustices. Rothberg’s claim offers an alternative to the perpetrator-victim binary. But his relational approach could create a situation in which the perpetrator becomes a victim under other circumstances.

[1] The way the dancer moves in the short clips recalls Giorgio Agamben’s ‘Notes on Gesture’ and the connections he drew between the early cinema experiments of Marey and Lumiere and Tourette Syndrome (named after the French neurologist Georges Gilles de la Tourette.)

[2] https://www.calvertjournal.com/articles/show/7805/turbofolk-serbias-weird-wonderful-pop-music; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serb_Volunteer_Guard

[3] https://balkaninsight.com/2014/12/08/arkan-s-paramilitaries-tigers-who-escaped-justice/. On December 28, 2022, Rolling Stone published the article ‘The DJ and the War Crimes’, the result of an eleven-month collaboration between the magazine and the Starling Lab, https://investigation.rollingstone.com/dj-photo-war-crimes-bosnia/.