*Dit voorjaar werd de internationale kunstwereld opgeschrikt. Vierentwintig werken uit de Belgisch-Russische verzameling Toporovski, die getoond werden in het Gentse Museum voor Schone Kunsten, alle van de hand van kunstenaars uit de Russische avant-garde, zouden vervalsingen zijn. De werken waren binnengehaald door MSK-directrice Catherine De Zegher. Een mediastorm ontstond, De Zegher werd in haar functie geschorst door het Gentse stadsbestuur. Ondertussen werden al een aantal werken door experts onderzocht: ze blijken alvast effectief geschilderd in de periode waaraan ze toegeschreven zijn. In onderstaande tekst spreekt Catherine De Zegher voor het eerst sinds haar schorsing.*

Fake art or fake news?

The Russian Avant-garde at the MSK Ghent

Over a period of years as Director I had developed a masterplan for the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent, in which I had programmed a series of international exhibitions for 2016-2020, such as ‘Medardo Rosso, Pioneer of Modern Sculpture’ and ‘From La Tintoretta to Artemisia Gentileschi’ in 2018; ‘Collage through the Centuries’ and ‘The Russian Avant-garde: From Icon to Square’ in 2019; and ‘Van Eyck: An Optical Revolution’ in 2020. As a part of this schedule the exhibition program for 2017 had been established celebrating the 10th anniversary of the 2007 museum renovation. With my colleagues acting as the curatorial team of the celebration, I had decided to undertake a radical makeover of the entire museum in order to display its rich collection in full glory. Among other new elements, the historical sequence was illustrated with specific colours for the different eras and reorganized with the insertion of some thematic galleries and several juxtapositions of old and new art in a relational manner. Innovative projects were included inside the historical collection to make the museum visit more vivid and accessible in the light of current study. For example, three projects by contemporary artists Ria Verhaeghe, Patrick Van Caeckenbergh and Luc Tuymans contributed to bringing the past into the present and to enhance the journey through the collection.

It is in this context, in Spring 2017, that I followed up on the request of the Minister of Culture, Sven Gatz, to visit the Toporovski Collection in Brussels. At the Minister’s prompting and after several meetings a basis of trust was reached and I was given access to the archival and art historical research materials of the collectors, Igor and Olga Toporovski-Pevsner. In accordance with the established principles of due diligence and in the light of what I was discovering and starting to analyse, I came to form the view that having access to such an interesting collection of Russian artworks and archives in Belgium opened up possibilities and a unique opportunity to present one of the critical art movements of the 20th century – an art movement that otherwise is out of reach for a museum with limited budgets and connections as the MSK in Ghent. Together with the Senior Curator of the museum and, at this stage, two art historians valued for their experience with the Russian avant-garde, we saw the potential of the material we were examining to contribute to our organizing of the large-scale exhibition projected for 2019, titled ‘From Icon to Square’, in which a new vision would be developed with regard to the Russian avant-garde, and in which some works of the Toporovski Collection could be integrated. I talked at length with the collectors about their passion and motivation behind the collection and the Dieleghem Foundation, the development of the new museum they planned in Brussels, and the provenance and significance of their works.

During these conversations, mainly elaborating on the 2019 exhibition, I was struck by their knowledge of modern art history, their works and archives. It was at that time, once we had gathered a lot of material, that we considered also having, among the interventions for the general re-installation to open in October 2017, a room dedicated to the Russian avant-garde given its profound influence on the development of art in Europe during the modern era. In this way, the room dedicated to Belgian Modernism could be seen next to the room devoted to Russian Modernism. We hoped that our work on the complete re-installation would help to propel the MSK further into the international limelight. Indeed, it was immediately and widely acclaimed for its daring beauty – the press even wrote that it was the most interesting and stunning museum installation in Flanders. And in the 2018 report of the selection committee for museum grants, the Ministry of Culture could read that the MSK was defined as one of the best, if not the best, museum in Flanders on all accounts.

Unearthing the facts is for you

Soon after the opening, rumours began to be circulated by some galleries and art dealers, who claimed to specialise in Russian avant-garde art, with regard to the authenticity of the works from the Toporovski Collection on view at the MSK. The absence of a convincing factual base for such allegations, when the rumours were repeated and elaborated in an orchestrated media attack, could not prevent the claims of non-authenticity from becoming the overarching theme. As of mid-January 2018, and continuing over seven weeks with around forty articles, the media sensation was whipped to a frenzy of vituperative innuendo and accusation. At first, my voice was not heard. Then as a civil servant, I could not speak up nor did I want to become part of a polemic based on an evident falsehood. I have thus remained silent throughout a process that has been ongoing for more than eight months. This has come at great cost to my health, my work, and my reputation. In effect, I have been exiled from the MSK and gagged since March 2018. And most shockingly of all, I have been subjected to an extraordinarily virulent and rare witch-hunt that resulted in a trial by media. And this is no exaggeration, as those familiar with the story will attest.

But I cannot remain silent any longer. The time has come to speak because an injustice is being committed that has profound implications beyond its cruel impact on my life. The plain fact is that there are two egregious consequences if someone doesn’t speak out. Firstly, people who love art and believe in its true value, those who come to the museum for enlightenment, education, and beauty, the citizens of Ghent and Belgium today, are denied the opportunity to discover and truly appreciate these outstanding works of art of the early 20th century – works that will never be shown again at the museum and have never before been seen together since they were made in the first decades of the 20th century. Secondly, should this polemic of market manipulation, hand in hand with one-sided opinion warfare, and this bloodlust of the witch-hunt continue and even triumph, the works of artists of true genius would be denied and a part of art history would be lost. Actually, a part of all our history would be erased: the corpus of the Russian avant-garde is indeed far larger than we know in the West, and is only slowly being revealed.

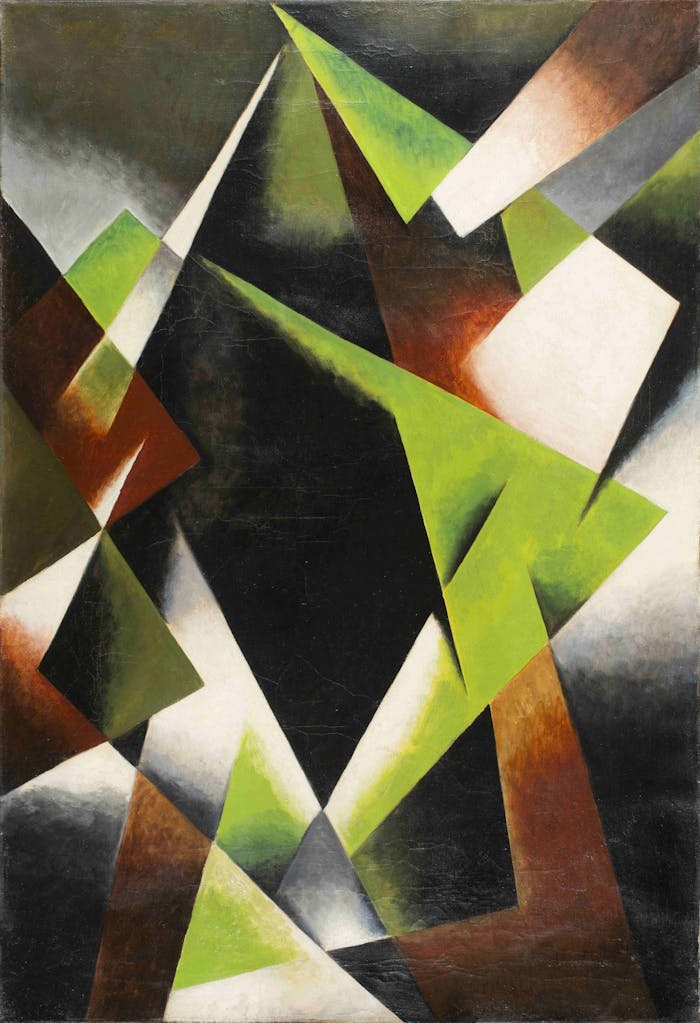

Silence will not do. Do you realize what is going on? Those with an interest in this case and in the purposes for which it has been used—financial and political—know and are still silent about the facts. Today, there is more than the existing result of our initial research that provided art historical and archival evidence. There is now new material-technical evidence, based on specialised laboratory research, that shows clearly and incontrovertibly that the works so far tested are genuine, they are authentic and proven to be so. Furthermore, this new material-technical evidence specifically pertains to the works that were most maliciously attacked in the media. I am not speaking for the collector nor am I speaking for the museum, I am speaking for those who love art and beauty and truth; I am speaking for all of the audiences for this art today; for the amazing female and male artists who made these works—Liubov Popova, Vladimir Tatlin, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Natalia Goncharova, Olga Rozanova, Alexandra Exter, Kazimir Malevich…—in a time of upheaval and under great pressure; and I also speak for those who will come to see and understand these Russian works beyond our lifetime. We must not allow the truth of this precarious beauty to be destroyed on the basis of unfounded allegations and speculations. Now others need to examine how this travesty of denial has been promoted. I have my own story, based on thorough research, known facts, and new scientific evidence confirming my judgement and conviction. However, there is an overarching duty we have that must guide and inform our examination of the facts: at the centre of all of this is that these are masterworks made by artists whose lives were often lived in fear, poverty, and sometimes in prison, and who faced immense challenges in a world in turmoil: they and their genius must not be denied in death as they so often were in life.

I am no Joan of Arc, a woman ready to be burnt at the stake, but an Amazon on the side of history and art history. I learned that a person wrote to one newspaper: “You are doing with Catherine de Zegher what Stalin did with Malevich! Stop it! You are on the wrong side of history!” Yes, I believe in art’s profound meanings that sometimes make demands of us. I have fought all my life, in my work, for beauty that is denied, I have fought for those whose work has been eclipsed or marginalized, for women’s art that our societies too often ignored or suppressed, and for the art of communities and cultures that were thought to be outside the mainstream of the Western canon. What I have done with the Russian avant-garde works is no different from what I have done to assert the true meanings of these other artworks. I have unearthed and uncovered, and tried to bring from the shadow into the light here, as always before, work and truth that is similarly denied and dismissed. The time has come for others to speak, not in denial or with the poisonous reasoning of vested interest, but in clear-sighted examination of the facts.

The Russian works that were exhibited and that came to be, and continue to be, the subject of an attempted malign market manipulation and of a vicious media hype are iconic in the ferment of their revolutionary creation. The scenario of the orchestration is always similar and has been used before by the same dealers in their attacks on other museums showing avant-garde work, most notoriously, at Tate Modern in London and the House of Mantua in Italy. It was repeated at the MSK Ghent. The beauty and ingenuity of the avant-garde art was clear to me from the start and even more so as my study and investigation continued. Today, the scientific evidence provided by unimpeachable authorities confirms every claim I have made for the works based on the art historical and archival evidence, certainly of all the works for which the tests have been completed up until now. But those who know this, and many do, are remaining silent.

The scientific evidence is there and it is up to you to face it…

And to come to terms with its implications—not only implications for art but the implications of what this affair has said about our democracy and the ease with which the public conversation was hijacked and manipulated by players in Flanders and abroad. Museums worldwide have reasons to be alarmed by this case, but all of us who value the reasoned examination of facts untainted by the venal influence of corrupt and opaque purposes should be concerned by what is happening. The story of our time is increasingly a story of hidden agendas, of deception, and the manipulation of opinion.

The authentication of historical art works can appear an arcane matter that must be left to ‘experts’. Many are understandably reluctant to enter into the often-complex discussion of attribution. But this case has blown wide open, if briefly, the doors of a murky and closed world in which the market is rigged, not only by those buying up works but also by those trashing works they don’t possess, regardless of whether they are authentic or fake. The story of the Russian works at the MSK Ghent is worthy of the plot of a thriller novel. Artists having impoverished lives in an extraordinary time, amidst social and political chaos, made outstandingly beautiful and meaningful works that were doomed to be condemned, shunned, and forbidden by Stalin and the apparatus of the State. Many of the objects they made were destroyed while others were spirited away by people who refused to bow to the orders of their political masters. These objects were hidden in closed vaults and far regions of the Soviet Union. I have visited some of these places, such as The Museum of Nukus in Uzbekistan where I talked at length with its director, who had a difficult time in the past for harbouring works of the avant-garde and its pupils.

As the tides of history, of war and uncertain peace, washed over the continent during the 20th century, and as an empire rose and fell, in the ruins the hidden caches of these wonders have come to be revealed. At first surreptitiously, the once forbidden works were taken from locked and sealed vaults to be sold to those who understood their value. In fascinating detail, David Harel and Joseph Agassi shed light on the subject in their book ‘Malevich: The Lost Paintings’.

In the end, the facts are very simple and clear: if the works are objectively shown to be of a particular time, by scientific testing that now has extraordinary accuracy, performed in the leading specialist laboratories of unimpeachable reputation in Cologne and Paris, by scientists who, like me, have no financial interest in the outcome, the likelihood of their being false becomes vanishingly small. Eight works have been tested and analysed so far and all have been confirmed and placed in the era ascribed to them. I had the material-technical evidence pertaining to two works before the opening at the museum. When the analyses of the next paintings to be tested are complete there will be results for half of the twenty-four works that were exhibited. We have to ask: at the time they were made who would fake works that were not only of no financial value but also forbidden? Who would fake works that, while we now recognize them for their life and brilliance, were not only controversial but were soon to be condemned? The evidence of provenance, of art history, of archival documents, and, above all of the beauty we see is wholly proven by the age of the materials and dating of their use.

The full story of the Toporovski Collection at the Dieleghem Foundation and the works from the collection shown at the MSK will be revealed in the book to be published in the Spring 2019. You will find all the evidence and provenance: art historical, archival, and material-technical…Few works in any museum will have had such attention… and such rigorous proof!

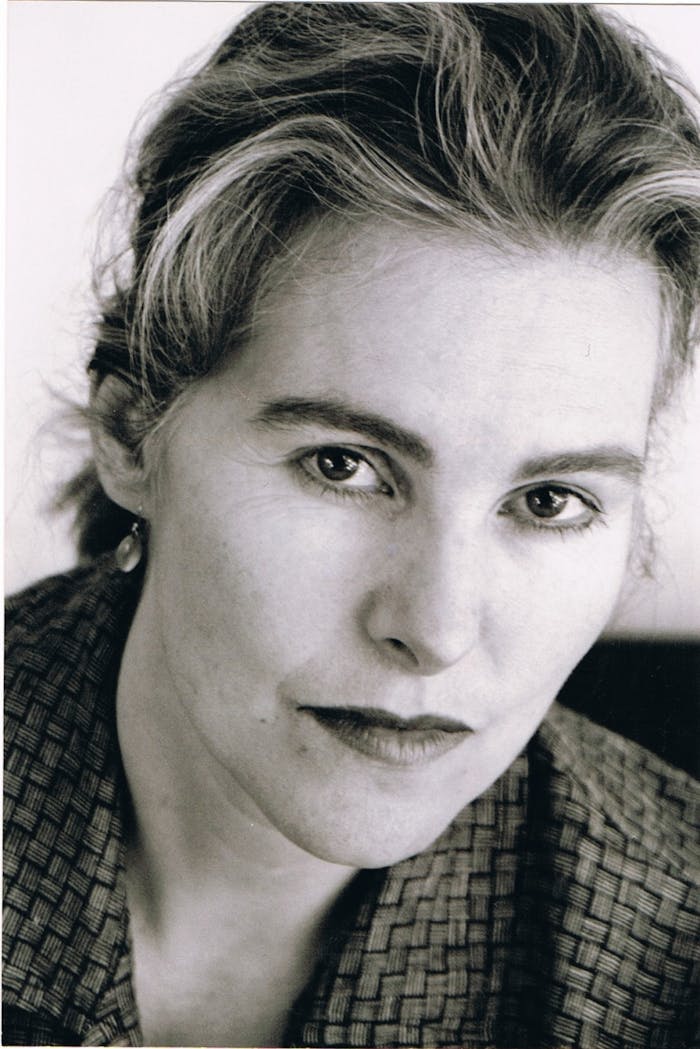

*Catherine DE ZEGHER*